What exactly does the

BBC

What does it think? Why should license-payers bear the cost for a news website published in West African Pidgin — a language that originated as a simplified version of English and was not meant to be used in writing?

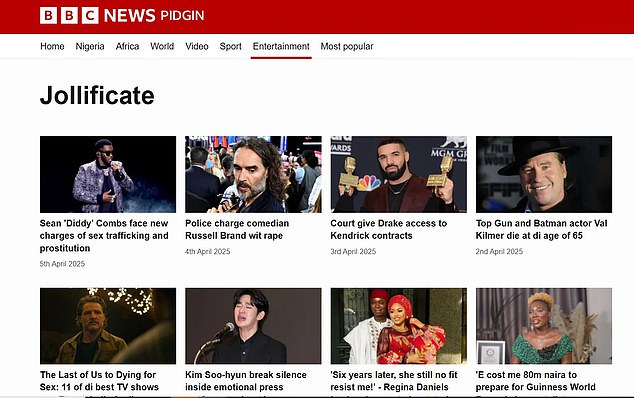

Astonishingly, the World Service now runs a full Pidgin version of the BBC news site, complete with online stories and headlines transcribed into what was once known as Guinea Coast Creole.

The outcomes can be absurd. Pidgin refers to a colloquial form of speech characterized by a reduced lexicon and basic grammatical structures used primarily in informal settings. This vernacular lacks the complexity needed for covering news effectively; consequently, numerous headlines only slightly deviate from conventional English, often differing merely through minor alterations in spelling.

‘Top Gun actor

Val Kilmer

die at di age of 65’ needs no translation. Nor does, ‘Why

Prince Harry

dey quit di Sentebale charity wey e set up in Diana honour’. Of course, ‘di’ is a phonetic rendering of ‘the’, and ‘wey e’ is ‘which he’.

Others might be a little more puzzling, though you’ll get the gist. ‘Wetin

Putin

tok wey make Trump vex’ announces a report on the

Ukraine

war, informing us what Putin said to make Trump angry.

‘British boarding schools have started reopening.’

Nigeria

We learn that they are eager to draw in students from West Africa — indicating the schools have a keen interest in attracting these pupils.

A number of the translations are quite hilarious. The entertainment news section is titled ‘Jollificate,’ which signifies ‘making cheerful’ – this doesn’t really fit well on a page filled with reports about celebrity fatalities, legal disputes, and conflicts, including headlines like, ‘Five Tins We Know About.’

Gene Hackman

and im wife death’.

Certainly, I grasp Pidgin quite well. Having grown up in Ghana, I was frequently exposed to it. Within a large area featuring numerous indigenous dialects intertwined with official languages, it serves as an effective means for individuals to communicate, regardless of their origin.

Approximately 75 million individuals in Nigeria can comprehend it, but this does not render it suitable for use by the BBC News.

English is the official language of Ghana, though many people also speak Twi, Ewe, Fante or Ga.

It’s also common to hear Hausa and sometimes even Yoruba, with the latter originating in neighbouring Nigeria. And that’s just a few of them.

It comes as no surprise that British sailors found it simpler to promote a fundamental English lexicon and grammar, which mixed with various African words over time.

It was never meant to be written down, which is why it doesn’t have strict guidelines or spelling conventions. You can’t even find it listed as an option.

Google

Translate.

The pronunciation clearly has an African influence as well, a characteristic it also shares with West Indian Patois.

At the playground, we occasionally used Pidgin just for kicks. However, I would never consider employing it at home. It’s somewhat crude and entirely lacking in politeness—similar to cursing in front of your folks. While everyone knows how to use it, there’s an appropriate moment and setting for it.

Similar to swearing, this behavior is considered rather unrefined for women. You’re far more probable to overhear a group of young men bantering in Pidgin if their girlfriends are not present.

For instance, you would never hear the President of Nigeria deliver a speech in Pidgin, or even use it when addressing anyone.

As I’ve mentioned before, this language carries a dark past. It developed during the peak of the slave trade in the 1700s and 1800s as a means for British merchants to communicate business matters with African traders and tribal chiefs—matters that frequently included the exchange of countless lives through the trafficking of humans.

Only someone spectacularly missing the point would try to codify it into something readable. And that someone is the BBC World Service.

Eight years ago, they introduced their Pidgin service with significant investment as part of the BBC’s $375 million international growth initiative. Despite announcing earlier this year that the World Service plans to cut 130 positions to save approximately $7.8 million annually, the news website will likely stay accessible.

The significant worth of the World Service lies in the international impact it provides for Britain.

Many individuals in West Africa depend on this source for impartial and rigorously verified information. The platform offers content in Yoruba and Igbo, along with various other languages throughout the continent like Amharic and Afaan Oromo.

Ethiopia

, and Tigrinya in Eritrea.

These services are the ones that ought to be preserved, rather than Pidgin. Headlines like “17 facts you need to know before the Oscars” have an uncomfortable undertone of racism, as though African viewers wouldn’t comprehend “before the Oscars.”

To understand how patronising it all is, imagine a news website written in the Geordie dialect: ‘Ah dinna believe ye! Ant an’ Dec’ve won anutha aword. Is this a joke like?’

Even a born-and-bred native of Newcastle would have to sound out those words mentally to grasp the meaning. Dialect should be spoken, not written. On the printed page, it takes on a mocking tone.

The BBC is widely seen abroad as the last bastion of the King’s English.

That reputation is weakened by the BBC World Service’s rather odd choice to consider Pidgin as equally valuable as other languages.

Any other nation would be shocked. Consider how offended the French would feel if the BBC released a site in Franglais for expatriates.

in Provence. Better to laugh it off than be offended, though. This headline last month made me howl with laughter: ‘Muslim

transgender

TikToker dey sentenced to prison after e tell Jesus to go cut im hair.’

The story goes on to explain that Ratu Thalisa, an Indonesian transwoman in Sumatra, was livestreaming a video chat to her fans when one man suggested she should get a haircut. Aggrieved, Thalisa retorted that if she needed a haircut, so did Christ.

The result? A prison sentence of two years, ten months for disturbing public order and religious harmony. ‘Di court ruling bin come afta multiple Christian groups bin file police complaints against Ms Thalisa for blasphemy,’ the report continued. She was found ‘guilty of spreading hatred under a controversial online hate-speech law.’

That last line reveals how ridiculous it is to ‘translate’ complex English into Pidgin. It has no equivalents for words such as ‘online’, ‘hate-speech’, or even ‘controversial’.

Equally suspect are the spellings imposed by the BBC. There’s no reason to write ‘continue’ as ‘kontinu’, as if a Pidgin speaker would not be able to recognise the correct spelling.

This standardized version was created by the BBC out of a sense of smug moral posturing. If individuals who genuinely use Pidgin had desired a standardized format, they would have likely developed it themselves as part of an organic local effort.

They wouldn’t have had to refer to the World Service, an entity headquartered in

London

If the BBC had paused for thought, they might have recognized how colonialist their approach appeared.

However, as usual, Auntie believes she knows best – which is her opinion.

Read more